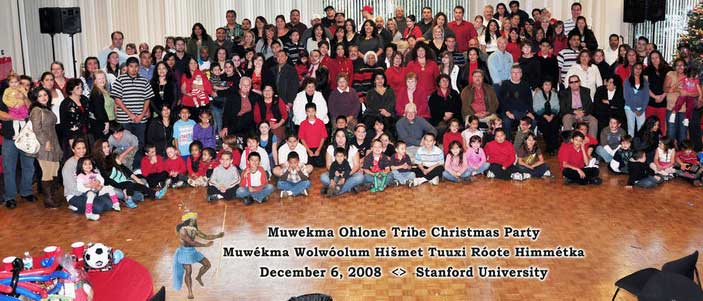

Recognition Process

During the early 1980’s, many Muwekma families came together to continue to conduct research on their tribe’s history and genealogy, and they also considered applying for Federal Recognition. Between 1982 and 1984, the Muwekma Tribal Council was formally organized. By 1989, the Tribal Council passed a resolution to petition the U.S. Government for Federal Acknowledgement.

Muwekma Ohlone Tribe Petition for Recognition delivered to President Bill Clinton

January 25, 1995

On January 25, 1995, the Tribe’s historical petition was submitted during a White House meeting of California Indian leaders. Additional research and documentation continued to be submitted, and on May 24, 1996 the BIA’S Branch of Acknowledgement and Research (BAR) made a positive determination of “previous unambiguous Federal Recognition” (under 25 CFR 83.8) stating that:

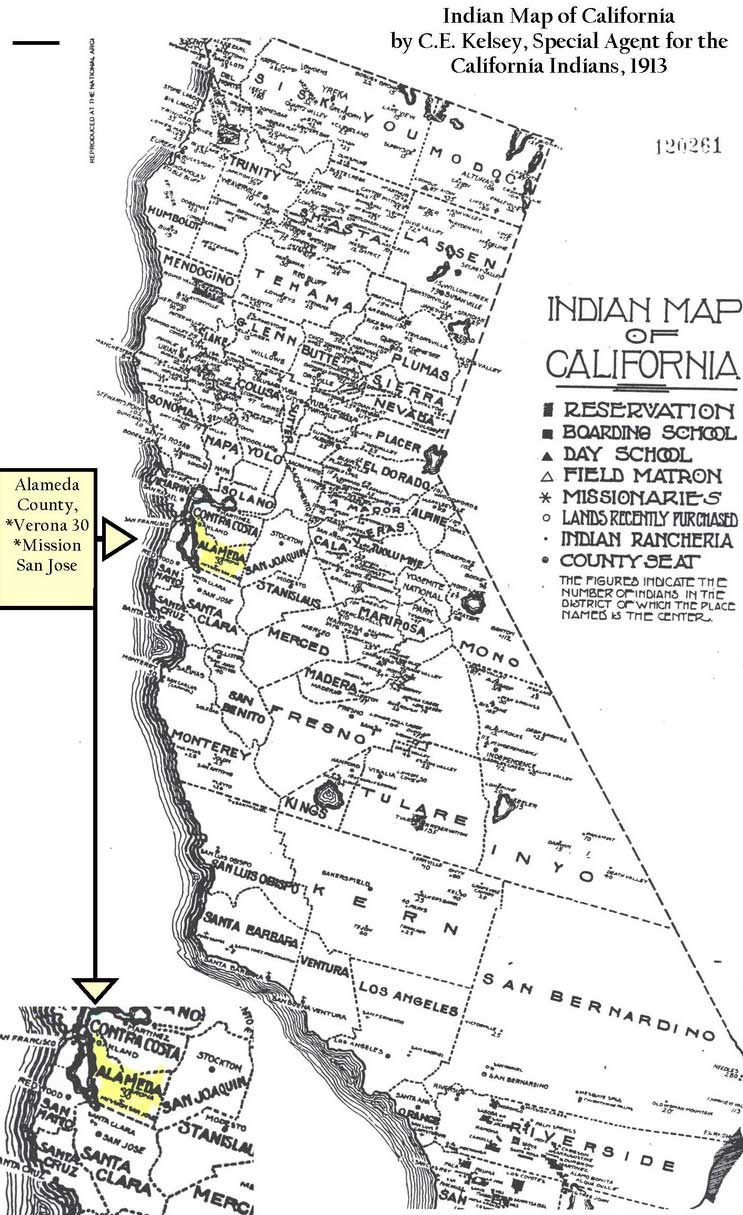

“Based upon the documentation provided, and the BIA’s background study on Federal acknowledgement in California between 1887 and 1933, we have concluded on a preliminary basis that the Pleasanton or Verona Band of Alameda County was previously acknowledged between 1914 and 1927. The band was among the groups, identified as bands, under the jurisdiction of the Indian agency at Sacramento, California. The agency dealt with the Verona Band as a group and identified it as a distinct social and Political entity.”

Even after obtaining their positive determination of “previous unambiguous Federal Recognition” the Muwekma Tribe still had to submit additional documentation (total of six linear feet) in order to satisfy the BAR’s seven mandatory criteria (25 CFR 83.7) Almost two years later, on March 26, 1998, as a result of submitting several hundred pages of additional documentation, Deborah Maddox, Division Chief of Tribal Operations, issued a letter to the Tribe stating that:

“A review of the muwekma submissions shows that there is sufficient evidence to review the petition on all seven of the mandatory criteria. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is placing the Muwekma petition on the ready for active consideration lists as of March 26, 1998.”

After being placed on “Ready Status,” the Muwekma Tribal Council reviewed the Federal Registry and counted the number of tribes on both the “Active Consideration” and ‘Ready Status” lists. Muwekma was about the 22nd tribe in line after factoring in both lists. Based upon the speed that BAR was processing tribal petitions, at the rate of approximately 24 plus years before it would begin to consider the Muwekma Tribe’s documented petition. The Tribal Council also inquired if there were any other tribes on either list with a formal determination of “previous unambiguous Federal recognition.” The answer was “no”. As a result, the Muwekma Tribal Council decided that a wait of 24 plus years was not acceptable to the Tribe, and therefore, sought alternative remedies. After failing to attain a date from the BAR (now called Office of Federal Acknowledgement) as to when the Tribe’s petition would be reviewed, the Council had no choice except to consider legal action.

On December 8, 1999. the Muwekma Tribal Council and its legal consultants filed a law suit against the Interior Department/BIA – naming secretary Bruce Babbitt and Assistant Secretary of Indian Country and in the Courts. On June 30, 2000, Federal District Judge Ricardo M. Urbina, ruled in favor of the Muwekma Tribe and ordered the interior Department to formulate a process to expedite the Muwekma’s petition. On July 28, 2000, based upon the BIA’s findings, Justice Urbina wrote in the introduction of his Memorandum Opinion Granting the Plaintiff’s Motion to Amend the Court’s Order that:

“The Muwekma Tribe is a tribe of Ohlone Indians indigenous to the present-day San Francisco Bay area. In the early part of the Twentieth Century, the Department of the Interior (“DOI”) recognized the Muwekma tribe as an Indian tribe under the jurisdiction of the United States.” (Civil Case No. 99-3261 RMU D.D.C)

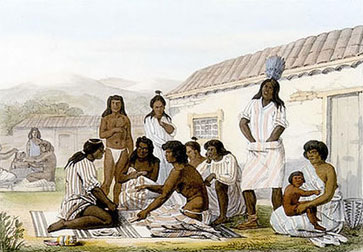

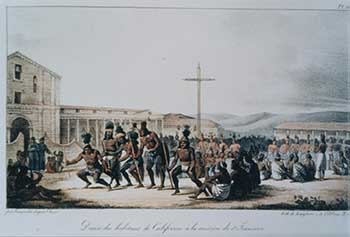

Drawing by Louis Andrevitch Choris

Between September and October 2000, following the court order, and after consultation with BIA/BAR staff, Muwekma submitted another two Exhibit volumes which demonstrated how the 400 plus enrolled members of the tribe are descended from full-blooded ancestors or siblings of those ancestors listed on the three Federal Indian Population Schedules (Census) of 1900 and 1910 for Washington, Murray and Pleasanton Townships, Alameda County, and from Kelsey’s 1905-1906 Special Indian Census. As a result, on October 30, 2000, the BAR and Tribal Services Division of the BIA responded to the Court Order and issued the following questions, answered statements and conclusions:

“Do current members ‘descend from’ a previously recognized tribal entity? … … When combined with the members who have both types of ancestors, 100% of the membership is represented Thus, analysis shows that the petition’s membership can trace (and, based on a sampling, can document) its various lineages back to individuals or to one or more siblings of individuals appearing on the 1900, “Kelsey”, and 1910 census enumerations described above.”

Juarez, 1948

As a result of the Congressionally mandated 1998 Advisory Council on California Indian Policy’s finding, Congressman George Miller’s office drafted proposed legislation in 2000 that sought to restored several of the “Terminated” California Indian Tribes as well as realfirm the status of several previously Federally Recognized Tribes whom were never Terminated by the U.S. Congress, including the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe:

2000 – Restoration of Terminated California Tribes and California Tribal Status Clarification Act – Proposed by Congressman George Miller. “Title II – California Tribal Status Clarification Act Sec. 202. Findings: (4) The Muwekma are the descendants of the native peoples who occupied the southern, eastern and western regions of the San Franscisco Bay Area, including all of what is now San Fransico, San Mateo, Alameda and Contra Costa Counties, much of what is now Santa Clara County, and parts of Santa Cruz, San Joaquin, Napa and Solano Counties. Jalquin / Yrgin, Alson / Tamien, Suenen, Chupcan, Choquoime and Nototomine. Spanish missionaries forced the ancestors of the Muwekma Tribe into the Mission Dolores, San Jose and Santa Clara in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In the 1830’s the Mexican government secularized the missions which resulted in the exclusion of the Muwekma from the three Bay Area missions and their resettlement in a number of rancherias in the Alameda County, including the Alisal Rancheria near Pleasanton, the Del Mocho Rancheria near Livermore, the El Molino Rancheria near Niles, as well as on rancherias in sunol and San Leandro / San Lorenzo, The Muwekma People continue to reside in their aboriginal territory in the San Franscisco Bay Area.

(5) The United States recognized all four tribes in the early part of the century as politically identifiable bands of Indians under its jurisdiction and eligible for statutory benefits and services. The Koi people were recognized as the Lower Lake Band, The Tsnungwe as the Trinity Tribe of Humboldt County and the Burnt Ranch, the Muwekma as the Verona Band of Alameda County and the Dunlap as the Dunlap Band of Monos.

(6) The United States recognized the four tribes as eligible for the purchase of lands under the provisions of various Appropriations Acts allocating funds to purchase lands for homeless Indians in California. While the BIA recognized the Muwekma, Tsnungwc and Dunlap as tribes eligible for the purchase of land under these Acts, no land ever was purchased for them. … .

(7) The members of the Tribes or their ancestors are enrolled as California Indians by the BIA Pursuant to the Act of May 18. 1928, ch. 624, 45 Stat. 602 and its amendments (codified at 25 U.S.C 651 ct seq.) authoring a claims case to be brought on behalf of all California Indians for lands reserved in eighteen treaties negotiated with California tribes in 1851-1852 but never ratified by the U.S. Senate.

(8) Congress has never terminated or express an intent to terminate the status of the Lower Lake Koi Tribe, the Muwekma Tribe or the Tsnungwe Council. Nevertheless, the Bureau of Indian Affairs has refused to deal with the Tribes as federally recognized tribes. Not with standing the denial of federal benefits services, and protection the Tribes have continued to maintain social and political ties from since the dates of last recognition.”

On July 25, 2002, California Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren issued the following statement in support of the Muwekma’s restoration on the floor of the House of Representatives:

“The Muwekma Ohlone Indian Tribe is a sovereign Indian Nation located within several counties in the San Franscisco Bay Area since time immemorial. … The Congress of the United States also recognized the Verona Band pursuant to Chapter 14 of Title 25 of the United States Code, which was affirmed by the United States Court of Claims in the Case of Indians of California v. United States (1942) 98 Ct. Cl.583”…

Meanwhile, as a result of inconsistent federal policies of neglect toward the California Indians, the government breached the trust responsibility relationship with the Muwekma tribe and left the Tribe landless and without either services or benefits. As a result, the Tribe landless and without either services or benefits. As a result, the Tribe landless and without either services or benefits. As a result, the Tribe has suffered losses and displacement. Despite these hardships the Tribe has never relinquished their Indian tribal status and their status was never terminated.”…

Simultaneously, in the 1980’s and 1990’s, the United States Congress recognized the federal government’s neglect of the California Indians and directed a Commission to study the history and current status of the California Indians and to deliver a report with recommendations. In the late 1990’s the Congressional mandated report – the California Advisory Report, recommended that the Muwekma Ohlone tribe be reaffirmed to its status as a federally recognized tribe along with five other Tribes, …”

I proudly support the long struggle of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe as they continue to seek justice and to finally, and without further delay, achieve their goal of their reaffirmation of their tribal status by the federal government. This process has dragged on long enough. I hope that the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Department of Interior will do the right thing and act positively to grant the Muwekma Ohlone tribe their rights as a Federally Recognized Indian Tribe. … To do anything else is to deny this tribe justice. They have waited patiently and should not have a wait any longer.”

On August 29, 2002, California Lt. Governor Cruz Bustamante wrote a letter supporting the Tribe to Assistant Secretary – Indian Affairs, Neil McCaleb:

“I write to urge you to support Petition #111 by the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe for reaffirmation of Federal Acknowledgement. The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe meets all of the criteria for reaffirmation set by the court as well as the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ acknowledgement criteria. The tribe is a previously recognized tribe. It has demonstrated that it has had a trust relationship with the United States from 1906 to the present and Congress has never terminated their relationship. The Tribe’s membership descend from an historical tribe and they are not members of any other Federally recognized tribe. After compiling data and completing extensive research, the Muwekma have presented a compelling case for the tribe’s Federal Acknowledgement. I respectfully urge you and the Bureau of Indian Affairs to Carefully review their Petition.’

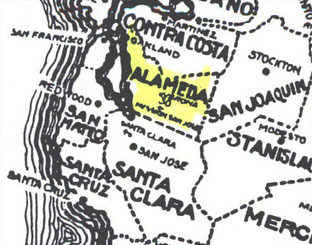

Special Agent forn the California Indians, 1913

Alameda County,

*Verona 30 * Mission San Jose

On September 6, 2002, the BIA issued its Final Determination against the future of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe. The BIA agreed that the Tribe is a historic and previously Federally Recognized Tribe. It also confirmed that the Tribe. It also confirmed that the Tribe was never legally ‘terminated’ by any Act of Congress or Executive Order. The BIA determined that at least ‘99% of the members descend from the previously Recognized tribe.” However, the BIA staff decided not to review and weigh the submitted evidence and reaffirm Federal Recognition back to our Tribe. In retrospect, it appears now that the same BIA staff and solicitors, whom bitterly opposed the Muwekma Tribe in their lawsuit were the same people who made the administrative Final Determination against Muwekma. The Bureau’s Decision Maker, Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs, Neil McCaleb, refused to review any of the Tribe’s evidence himself, but instead just rubber-stamped the final recommendations made by BIA staff. The Tribe was never allowed to challenge the BAR’s findings nor present any of the evidence to McCaleb directly. Clearly, the 25 CFR Part 83 administrative process is far from being balanced and impartial.

Nonetheless, under the BAR’S Summary Conclusion’s Under the Criteria (25 CFR 83.7) of the Muwekma petition, the BIA did in fact determine that: “The review of all evidence in the record concludes that the muwekma petitioner has satisfied the requirements of 25 CFR 83.7 (d), (e), (f), and (g). That is, the petitioner’s constitution and enrollment ordinance describe its membership criteria and governing procedures, its members have demonstrated their descent from the historical tribe (in this case, from the Verona band last acknowledged by the Federal Government in 1927…)” …”in addition, Congress may consider taking legislative action to recognize petitioners which do not meet the specific requirements of the acknowledgement regulations but, nevertheless, have merit.”(Pages 7-8)

At this point, the Muwekma had exhausted the regulatory process and though this arduous and demeaning process, the Tribe encountered the very same “gross negligence” and “crass indifference” with the current BIA bureaucrats and decision makers as it had encountered eighty two years earlier with Superintendent L. A. Dorrington in 1927, Even with the supporting evidence reported to the U.S. Congress in the 1998 Advisory Council on California Indian Policy reports on the present status of California Indians, this justice issue, like many other Native American civil rights and justice issues before it, has fallen upon deaf cars. The Congress once again has refused to act upon the very Commission that it had charged and funded with taxpayer’s money in order to correct what it has deemed “errors of the past.”

In the 1998 ACCIP report on Acknowledgement, entitled: Advisory Council on California Indian Policy Recognition Report – Equal Justice for California the Council issued the following conclusions about previously Federally Recognized Tribes in California whom were disenfranchised by Sacramento Superintendent, Lalayette A. Dorrington: “The Dorrington report provides evidence of previous federal acknowledgement for modern-day petitioners who can establish their connection to the historic bands identified therein. Clearly, the BIA “recognized” its trust obligations to these Indian Acts and the Allotment Act – to determine their living conditions and their need for land. The fact that some were provided with land and others were not did not diminish that trust. … Among those California Indian groups that have petitioned for federal acknowledgement, there are several who can trace their origins to one or more of the bands identified in the Dorrington report. The Muwekma Tribe is one whose connection to the Verona Band (id, at I) has been recently confirmed in a letter from the BAR, …”

The ACCIP completed its mandate to report back to the congress on the issues confronting California Indian tribes and the Federal Recognition Process. A copy of the 1998 ACCIP final report was submitted by the Tribe to the BIA as part of its response to the BAR’s initial “proposed Findings”. In their Final Determination the BAR made clear that it would not review or consider any evidence prior to 1927 and after 1985, even though it had encouraged the Tribe that it would do so during the Tribe’s Technical Assistance meeting on November 7, 2001. The BAR staff sidestepped their own recommendations by stating: “Given these conclusions of the proposed Finding under criterion 83.7 (a), that the period prior to 1927 is outside the period to be evaluated and that the petitioner met this criterion during the period after 1985, it is not necessary to respond to the petitioner’s comments and arguments for those two time periods.” (page 9)

On April 21, 2004, former Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs, Kevin Gover provided testimony before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs on proposed Senate Bill 297. In his testimony addressing the “structural issues with the Federal Acknowledgement Program” former AS-IA Gover provided the following statement:

“As has been well documented, I did not always agree with the judgements and opinions of BAR researches and the attorneys had been essentially unsuperivised for many years and that the Assistant Secretary’s office had become little more than a rubber stamp for their recommendations. …(page 3-4)

In his continued testimony on S. 297, former AS-IA Gover made the following points:

“… My primary disagreement with BAR staff related specifically to the assignment of weight to specific evidence, the inferences that could fairly be drawn from the evidence, and the degree of certainly about historical facts required by the regulation. I believe that BAR staff, being of trained historians, anthropologists, and genealogists, applied too difficult a standard. I believe they sought near certainly of the facts asserted by petitioners. They dismissed relevant evidence as inconclusive, even though conclusive proof is not required by the regulations. Moreover, BAR staff seemed thoroughly unwilling to give evidence any cumulative effect. While any given piece of evidence, when considered cumulatively, can make a sound case. … I do believe that, in accordance with their training, they applied a burden of proof far beyond what is appropriate and far beyond what is permitted by the regulations. …” (Page 5)

In former AS-IA Gover’s “Suggestions for Amendments” he forwarded the following:

“… First, I strongly believe that certain petitioners, which already have been denied recognition, should be permitted another opportunity under the revised process established by this bill. … Into this category I would place Mowa Chactaw. Finally, I remain convinced that the Chinook Tribe is deserving of federal recognition, and I believe that, if Assistant Secretary McCaleb had the resources provided by this bill available to him when he addressed the Chinook petition, the outcome well may have been different. There may be other tribes, such as the Duwamish and the Muwekma who should be eligible for reconsideration as well.” (Page 7)

In 2005, the Chair of the House Resources committee, California Congressman Richard Pombo wrote a letter of support on behalf of the Tribe to then Secretary of Interior Gale Norton Stating:

“As part of my Committee’s oversight of the procedures for federal recognition of Indian Tribes, I have heard testimony in a hearing earlier this year of the protracted litigation concerning the recognition of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe. The Tribe informs me that the Department of the interior has determined that Muwekma is a previously recognized tribe, federally recognized until 1927 also that no formal action by the Department and no Act of Congress removed it from recognition and that 99% of the members of the current tribe are direct descendants of the members of the recognized tribe.

The Muwekma Tribe raises the issue that, in a very similar situation, the Department reaffirmed the federally recognized status of the Lower Lake Koi Tribe and the lone band of Miwok in California by a letter signed by the then Assistant Secretary of the Interior restoring them to recognized without making them go through formal recognition procedures.

Despite numerous calls and letters from the Tribe, I understand these efforts at settlement have been largely ignored. I urge you to bring to resolution this dispute with the Muwekma Ohlone Trible If possible. My concerns stem from the fact that in continuing this litigation, only unnecessary time and expense will result and some settlement along the lines your Department has already considered may be the best result. Therefore, I would suggest, if possible, that the Department meet with the Tribe to pursue settlement opportunities. …” (Pombo letter to Norton dated June 30, 2005)

Mission Dolores, San Francisco, CA, circa 1822

Drawing by Louis Andrevitch Choris

On September 21, 2006, another victory was handed to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe by the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. Stating: The following facts are not dispute. Muwekma is a group of American Indians Indigenous to the San Francisco Bay area, the members of which are direct descendants of the historical Mission San Jose Tribe, also known as the Pleasanton or Verona Band of Alameda County (“the Verona Band”). … From 1914 to 1927, the Verona Band was recognized by the federal government as an Indian tribe.

Neither Congress nor any executive agency ever formally withdrew federal recognition of the Verona Band.

Upon remand, the Department must provide a detailed explanation of the reasons for its refusal to waive the part 83 procedures when evaluating Muwekma’s request for federal tribal recognition, particularly in light of its willingness to “clarif[y] the status of [lone] . . . [and] realfirm[] the status of [Lower Lake] without requiring [them] to. Submit . . . petition[s] under . . . Part 83.” Such an explanation may not rely on the fact that a “lengthy and thorough’ evaluation of Muwekma’s petition. At issue for the purpose of this remand is not whether the Department correctly evaluated Muwekma’s completed petition under the part 83 criteria, but whether It had a sufficient basis to require Muwekma to proceed under the heightened evidentiary burden of the part 83 procedures in the first place, given Muwekma’s alleged similarity to lone and Lower Lake.

In the Tribe’s final cross-motion before U.S. District Judge Reginald Walton, the Tribe has presented evidence and argued that:

“The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is entitled to summary judgement restoring it to the list of federally recognized tribes, Muwekma meets or exceeds the standard created by the Department’s decisions to realfirm the federal status of the Lower lake Rancheria (“Lower Lake”) and the lone Band of Miwok (“lone”). That standard set reaffirmation apart from acknowledged tribes off the Department’s lists of acknowledged tribes despite the absence of any act of termination.

The standards applied by Interior In those decisions relating to lone Band of Miwok and Lower Lake Rancheria are also applicable to Muwekma because of the similar historical circumstances that the three Tribes share.

Interior also failed to comply with these basic administrative requirements when informing Muwekma in the first instance of its decision not to consider Muwekma outside the Part 83 process. In the Explanation, Interior admits: “It is not clear from the documentary record how Muwekma was informed of the Department’s position” regarding Muwekma’s request for expedited procedures like those provided to Lower Lake and lone. Thus, there Is no ageney “Record of Decision” on this point, other than interior’s post hoc “Explanation” filed in response to this Court’s Order of September 21, 2006.

This Court recognizes that, “as the [D.C.] Circuit has clearly held, ‘where the agency has failed to provide a reasoned explanation, or where the record belies the agency’s conclusion, [this Court} must undo its action.”

The Bureau of Indian Affairs enrolled Muwekma members in the late 1920’s, 1930’s, 1950’s, late 1960’s and 1970’s under the California Claims Act of May 18, 1928, 45 Stat. 602, which required evidence of tribal membership. The Bureau also enrolled Muwekma children in BIA schools, yet another action that implies acknowledgement as a tribe, or at the very least an inference of an ongoing relationship with the government.

The Final Determination moreover arbitrarily and capriciously excluded from consideration evidence prior to 1927 and after 1985. These defects in the Final Determination illustrate interior’s violations of 5 u.s.c 554(d), the provision of the APA prohibiting an agency employee from participating both In decision-making and investigative functions. The same people who opposed Muwekma in its litigation to require Interior to timely review its petition, and lost, then helped draft the Final Determination against Muwekma, and are also on Interior’s brief here.

Interior in its dealing with Muwekma seems to be saying, if we didn’t treat you right before, you have no rights, and we can continue to mistreat you now. This is the opposite of the viewpoint that the Department applied to Lower Lake and lone. This Court should not allow such a calloused philosophy to dictate the outcome here, particularly where the law and facts so powerfully compel reversal.

Interior has failed to meet its burden under this Court’s Order and under the law. For all the reasons cited previously by the Tribe, further remand to the agency is no longer appropriate in this instance. The Tribe respectfully requests the Court to direct interior to realfirm the Tribe’s federal acknowledgement.

Moreover, the Court has the power and the obligations to undo an agency decision that does not meet this burden.”

On September 30, 2008 the US District Court in Washington, D.C. handed the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe another victory. Judge Reginald B. Walton opined: “These arguments, and the explanation from the Department giving rise to them, seemingly cannot be reconciled with the Court’s September 21, 2006, memorandum opinion. In that opinion, the Court noted that the defendants opposed the plaintiffs initial motion for summary judgment on three grounds, two of which concerned whether plaintiff was similarly situated to lone and Lower Lake for purposes of the plantiff’s constitutional and APA arguments. Specifically, ‘the defendants argue[d] that the Department ha[d] not treated like cases differently because by their very nature, federal acknowledgement decisions require hightly fact specific determinations,’ and “claim[ed] that the [the plaintiff] was not treated differently them similarly situated petitioners because groups demonstrating or alleging characteristics similar to [the plaintiff] are regularly required to proceed through the federal acknowledgement process.”

The Court rejected both of these arguments. It dismissed the defendants’ “hand-waving reference to ‘highly fact-specific determinations,” which, in the court’s estimation. “[did] not free the defendants” of their obligation to justify the decision to treat the plaintiff differently from lone and Lower Lake based on the administrative record for the plaintiff’s petition. Further, the Court found the argument “that groups such as [the plaintiff} have been regularly and repeatedly required to submit Part 83 petitions” insufficient “to refute [the plaintiff’s] claim that the Department has treated it differently from similarly situated tribal petitioners without sufficient jusitification.

The Court further noted in a footnote that the defendants “obliquely” provided a “basis for distinguishing [the plaintiff] and Lower Lake in their reply to [the plaintiff’s] opposition to their cross motion for summary judgement.” but also found this argument wanting. Specifically, the Court explained that: “First, and most obviously, [the defendants’ argument] pertain[ed] only to a difference between [the plaintiff] and one of the tribes with whom it [was] claiming to be similarly situated. The defendants [did] not assert any ‘highly fact-specific determination[]” that would explain why [the plaintiff] Is not similarly situated to lone in such a way as to require a reasoned explanation of the Department’s disparate actions. Second, the Department [did] not contend, here or in the administrative record, that it required [the plaintiff] and not Lower Lake to undergo the part 83 procedure because the latter, unlike the former, had received land in trust and had participated in an election.”

Having rejected all of the defendants’ arguments on the issue of similarity of circumstances ,the Court proceeded to find that “the Department . . . ha[d] never provided a clear and coherent explanation for its disparate treatment of [the [plaintiff] to submit a petition and documentation under Part 83 while allowing other tribes to bypass the formal tribal recognition procedure altogether.” Because there was “virtually nothing” in the administrative record that would “allow the Court to determine whether [the Department’s] judgement reflect[ed] reasoned decision making,” the Court concluded that it was ‘necessary to remand [the] case to allow the Department to supplement the administrative record in this regard.

In other words, the Court determined in its prior memorandum opinion that the defendants’ arguments to the effect that the plaintiff was not similarly situated to lone and Lower Lake were without merit, and remanded the case to the Department so that the Department could explain why it treated the plaintiff differently that other, similarly situated tribes. The necessary implication of both conclusions is that the Court found the plaintiff to be similarly situated to lone and Lower Lake.

Here, the Department’s explanation and the defendant’s arguments in defense of that explanation and in support of summary judgement in their favor would appear to run afoul of the law of the case established in this Court’s prior memorandum opinion. The Court concluded, implicitly if not explicitly, that the plaintiff is similarly situated to lone and Lower Lake, and remanded the case to the Department for the sole purpose of ascertaining a reason as to why the plaintiff was treated differently. Yet, the defendants do not even acknowledge that their arguments are inconsistent with the law-of-the-case, let alone provide a “compelling reason to depart” from it.

The defendants’ insouciance regarding the law-of-the-case Is particularly troubling because they appear to rely at least in part on administrative records for lone and Lower Lake that were not considered when the Department initially considered the plaintiff’s petition for recognition. This tactic harkens back to the defendants’ reply memorandum in support of their initial cross-motion for summary judgement, where they argued ‘that because the full body of administrative records regarding lone and Lower Lake [was] not before the Court, [the plaintiff] [could not] establish a violation of the Equal protection Clause or the APA simply by alleging that it ha[d] been treated differently than those tribes.”

The Court rejected that argument, explaining that “[w]hat matter[ed] . . . [was] whether the Department sufficiently justified in the administrative record for [the plaintiff’s] tribal petition its decision to treat [the plaintiff] differently from lone and Lower Lake.

The Court remanded this case to the Department so it could explain why it treated similarly situated tribes differently, not so that it could construct post-hoc arguments as to whether the tribes were similarly situated in the first place. It certainly did not remand the case so that the Department could re-open the record, weigh fact that it had never previously considered, and arrive at a conclusion vis-à-vis the similarity of the plaintiff’s situation to those of lone and Lower Lake that it had never reached before. The Court would therefore be well within its discretion to reject the defendants’ arguments outright, grant the plaintiff summary judgement with respect to its equal protection claim, and bring this case to close.”

Concluding Statement from the Muwekma Tribal Leadership

As a result of continuous gross negligence, crass indifference and deceitful actions by the Department of Interior, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is in the final throes of seeking resolution of its Federally Acknowledged status in Federal Court in order to correct the ‘administrative errors” perpetrated by the BIA in 1927 and in 2002. The Muwekma Tribe has waited since 1906 – one hundred and three years – for some semblance of justice. The Tribe has learned that if one follows the law and regulations, the Federal government and its bureaucracies, have the power to change all the rules of law midstream. Our people have suffered long enough under this “Apartheid system’ of government, and from the inequities perpetrated on us as the documented Aboriginal Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Makkin Mak Haššesin Hemme Ta Makiš Horše Mak-Muwékma, Rooket Mak Yiššasin Huyyunčiš Šiiniinikma!

We Will Make Things Right For Our People, and Dance For Our Children!

Drawing by Louis Andrevitch Choris

Our people are refugees within their aboriginal homeland. We will not stop fighting for our rights or for the rights of the other legitimate historic Tribes in California and elsewhere in the United States! We have suffered enough indignity by being totally disenfranchised within our children and our grandchildren. Regardless of the Federal Government’s recalcitrance to restore our Tribe’s status as a Federally Recognized Tribe, we will nonetheless persevere as the Aboriginal Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Region. We have lived here in our ancestral homelands within the greater San Francisco Bay for over 10,000 years and we have no intention of leaving, giving up or abdicating our Indian Heritage and Sovereign Rights!

The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe anticipates a positive outcome as a result of our multi-year law suit against the Department of interior/BIA. We anticipate that our Tribe we be restored to the list of Federally Recognized Tribes this year and when that joyful moment happens, we intend to celebrate our freedom from the odious yoke of oppression and exclusion that has been perpetrated upon our People since the invasion of California by European colonial powers and American Expansionist policies.

Please join with us in the everyday celebration of life, and embrace the acknowledgement that our ancestral homeland is indeed a wonderful place to live, for all us and our children. Aho!