Missions Land Rancheria

SECULARIZATION OF THE MISSIONS, MEXICAN LAND GRANTS AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE EAST BAY RANCHERIAS DURING THE AMERICAN CONQUEST PERIOD

Prior to the American conquest of California 1846-1848, some of the secularized Mission Santa Clara Indian families obtained formal Mexican land grants, while the majority of the others found refuge on the rancho lands of friendly California families in the East Bay.

Around the area surrounding Mission Santa Clara several Clareño Ohlone famiies were fortunate to be granted land grants by the California/Mexican government. In 1845, Governor Pio Pico granted the Ulistae land grant located within present-day City of Santa Clara to Marcello and two other Mission Santa Clara Indian men named Pio and Cristobal. Marcello’s parents Senneo and Pacaunga were from the San Bernardino Tamien speaking Ohlone Tribal group who were located in the Stevens Creek, Saratoga Creek and Pescadero Creek water shed region to the west/southwest of Mission Santa Clara. Pio and Cristobal lineages were traced through the Mission Santa Clara Raptism records to the Tayssen Ohlone Tribal group in the upland valleys east of San Jose near the Orestimba drainage. Rancho Ulistae measured half a league or approximately 2218 acres (Brown 1994)

Earlier, on February 15, 1844, another Clareño Ohlone Indian named Lope Yñigo, was issued title to 1959.9 acres (2.64 square miles) around present-day Moffett Field near Sunnyvale by Governor Micheltorena (Brown 1994). This land grant was called Rancho Polsomi y Pozitas de las Animas (Little Wells of Souls.) Apparently, Yñigo was recognized as a chief or “captain” of the ‘San Bernardino’ Ohlone People who originally occupied this area. He was baptized at Mission Santa Clara in 1789 (#1501). This land grant is also referred to as Yñigo’s grant, Yñigo Reservation (Thompson and West 1876 Historical Atlas Map of Santa Clara County)

Although reduced to approximately 400 acres, Yñigo’s claim came under review in the U.S. Land Commission of 1852 (Walkinshaw vs. the U.S. Governement, Posolmi, 125, Land Case 410) and he retained this portion of his land until his death on March 2, 1864. Yñigo was buried somewhere on his land which is now occupied by Moffett Field and Lockheed Corporation. After Yñigo’s death, it appears that his descendants may have moved to the Alviso rancho [(see U.S. Land Commission Index to land Grants 1852, U.S. General Land Office, Posolmi, 125, Land case 410); Bancroft 1886, Arbuckle 1968; sec: Thompson and West 1876 Map identifies Yñigo Reservation (Moffett Field); Yñigo Rancho by Pat Joyce; Obituary of Yñigo in the San Jose Patriot.

In 1844, Governor Manuel Micheltorena formally granted Rancho de los Coches (the Pigs), totaling 2219..4 acres, to a Mission Santa Clara Clareno Ohlone Indian named Roberto Balermino. Roberto had occupied this land west/southwest of confluence point – the meetings of Guadalupe River and Los Gatos Creek in downtown San Jose since 1836.

Rancho de los Coches, most probably within the aboriginal territory of Roberto’s direct ancestors that included the district that the Spanish priests called San Juan Rautista (not to be confused with Mission San Juan Bautista located south near Hollister). Roberto’s marriage to his first wife, Maria Estefana, connected him to the San Francisco Solano Tamien Ohlone speaking tribal group district to the west that included the present-day town of Cupertino (Brown 1994)

On the West Bay, another land grant was issued to another Clareño Ohlone Indian man and his family. Jose Gorgonto and his son. Jose Ramon, were granted Rancho La Purisima Concepcion by Governor Juan B. Alvarado on june 30, 1840. This rancho comprised 4,440 acres or 1 square league around the present day Palo Alto/Los Altos Hills area (Brown 1994)

During this post-secularization period, there were at least six other rancherias maintained around Pueblo de San Jose. One major Indian Settlement was located on the Santa Terasa Rancho (Bernal’s property) south of the Pueblo near the Santa Terasa Hills. Another was in the valley east of san jose called Palo Rancho, while a third was established along the Guadalupe River above Agnew on the Rincon de los Esteros Rancho. To the northwest in the present city of Cupertino was the Quito Rancho. In pueblo de San Jose, there was a settlement of ‘free Indians’ on the east side of present-day Market Street, and the sixth community was located further west along the banks of the Guadalupe River near Santa Clara Street in San Jose (King 1978, Winten 1978a)

Based upon his research, Milliken (1987) also discovered that in the 1840s a rancheria was established in the East Bay between Mission San Jose and Alameda Creek: One group of Indians established an independent community somewhere along the road north from Mission San Jose toward Alameda Creek during the 1840’s. The head of the community was Buenaventura, one of the few survivors of the original villages from the local ‘Estero’ area. or bayshore. Buenaventura had been baptized as a two year old at Mission San Jose in 1798 (JOB 161. Father Miguel Muro granted a license to Buenaventura, six other adult males and their families on 2 November 1844. His wife Desideria was of a family that had moved to the mission form the jalalon area, now eastern Contra Costa county. Buenaventura died in 1847. Desideria sold the group’s license to an American in 1849. The U.S. Land Commission of the 1850’s did not recognize the license as a valid land little, however [Land Case 290 n.d.:11] (Milliken, Leventhal and Cambra 1987)

The ‘Estero’ area along the bayshore included the Alson Chocheño/Tamien-speaking (bilingual) tribal group located along the lower Guadalupe River and the Tuibun tribal group of the Fremont Plain. As Discussed above both of these groups were first missionized at Mission Santa Clara and later went to Mission San Jose (Milliken 1983, 1991).

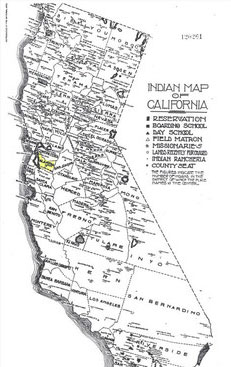

After the American takeover of California (1846-1848), there were Indian rancherias established on rancho lands in the East Bay. At least six Muwekma Indian rancheria communities emerged and maintained themselves during the 19th and early 20th centuries in the East Bay.

These rancherias were located at San Leandro/San Lorenzo (1830s-1860s). Alisal near Pleasonton (1850s-1916), Sunol (1880s-1917). Del Mocho in Livermore (1830s-1940s). El Molino in Niles (1830s-1910) and later a settlement in Newark (ca. 1914-present-day). A formal land claim was submitted for the San Lorenzo Rancheria by two East Bay Indians Anseto and Sylvester under the 1853 land claims commission (vol.7, page 441, Unclassified #97). Apparently, this claim was rejected by the US Claims Commission.

During the 1880s, George and Phoebe Apperson Hearst purchased part of the old (1839) Bernal/Sunol/Pico Rancho located south and west of Pleasonton, which included part the Alisal Rancheria with approximately 125 Indians residing there on the land.

Escaping the cold and foggy summers of San Francisco, the Hearst’s built their Hacienda de Poso del Verona (later renamed Castlewood Country Club) on this newly acquired land. Western Pacific Railroad also built a train station there so that the Victorian elite and other guests could visit with Mrs. Hearst at her Hacienda. This railway stop was named Verona Station. In 1905, as a result of the discovery of the 18 unratified California Indian Treaties (negotiated between 1851-1852), Mr. Charles E. Kelsey of San jose, who was originally affiliated as the Secretary of the Northern Association for California Indians was appointed Special Indian Agent to California by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (Indian Service Bureau) in Washington, D.C. in 1905, Agent Kelsey was charged by the Bureau to conduct a Special Indian Census, and identify all of the landless and homeless tribes and bands residing from south Central and Northern California.

Based upon the results of Kelsey’s Special Indian Census, in conjunction with the discovery of the 18 unratified treaties, Congress passed multiple Appropriation Acts beginning in 1906 on through 1937, for the purpose of purchasing “home sites” for the many intact California Indian tribes and bands.

One of the bands specifically identified by Agent Kelsey was the Verona Band of Alameda County residing near Pleasanton, Sunol and Niles (as well as other towns and ranches surrounding Mission San Jose). The direct ancestors of the present-day Muwekma Ohlone Tribe who comprised the Verona Band became Federally Acknowledged by the U.S. Government through the Appropriation Acts of Congress of 1906 and later years. Between the years 1906 and 1927, the Verona Band fell under the direct jurisdiction of the Indian Service Bureau in Washington, D.C., and by 1914, the Tribe was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Reno Agency and later again, transferred to the Sacramento Agency. During this time, the U.S. Government Indian agents attempted to purchase land for many of the Federally Recognized, but landless California Indian tribal bands.

To this effort, both the Indian agents and the Indian bands were faced with two basic problems:

- Many Californian landowners did not want Indians living next to them, so they would not sell suitable parcels of land

- Individuals who were willing to sell parcels to the government wanted greatly inflated prices, usually at prices much higher than what was allocated to purchase lands, or even the value of the land

In January 1927, Sacramento Superintendent Colonel Lafayette A. Dorrington (1923-1930) received a detailed office directive from Assistant Commissioner E. B. Merritt for him to list by county all of the tribes and bands under this jurisdiction that had yet to obtain a land base for their “home sites” This directive was issued to that Congress could plan its allocation budget for fiscal year 1929. Dorrington, who was chronically derelict in his duties, decided not to respond to this, as well as many other requests. By May 1927 under investigation, Dorrington yet again received another strongly worded directive from the Assistant Commissioner E. B. Merritt.

To this second directive, Dorrington reluctantly responded on June 23, 1927 by generating a report, which in effect, illegally, unilaterally and administratively terminated the rights of approximately 135 tribal bands throughout California from their Federally Acknowledged status by completely dismissing the needs of these landless tribal groups. The very first casualty on Dorrington’s “hit list” was the Verona Band of Alameda County. Without any benefit of an on-site visitation or conducting a needs assessment, which he was charged to do by the Assistant Commissioner, Dorrington opined:

“There is one band in Alameda County commonly known as the Verona Band, … located near the town of Verona; these Indians were formely those that resided in close promixity of the Mission San Jose. It does not appear at the present time that there is need for the purchase of land for the establishment of their homes.”

Thus with the stroke of a pen and without benefit of any due process or direct communication with the tribe or its leaders, the muwekma/Verona Band along with the other 134 tribal bands of California, inexplicably “lost” their formal statsus as Federally Recognized Tribes. Being reduced to a landless tribe of Indians, the Muwekma were essentially knocked off the Bureau of Indian Affair’s “radar screen,” and were considered ineligible to organize under the 1934 Indian Recognization Act. According to BIA staff in 1996, they stated that “the Bureau decided not to deal with the Tribe anymore.”

During the 20th Century, no other state within the U.S. had experienced the illegal termination of so many tribal groups. This massive dismissal was deliberately a result of the callons actions and dereliction of duty by an incompetent Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) agent. Several years later. Dorrington, still being prodded by BIA officials in Washington about the needs of the landless and homeless Indians in California, offered his opinion to Commissioner Rhoads. In a letter dated April 23, 1930 Dorrington wrote:

“… Kindly be respectfully advised that the matter of land purchase for homeless Indians has really been given constant and diligent attention throughout the current fiscal year to date and an earnest effort has been made to fully meet the needs of the Indians to the fullest extent without unnecessary or unjustified expenditure of funds, believing that to be the spirit of the law and your wishes in the premises. …”

“It has been my opinion, and therefore my belief, for several years that the best interests of the Indians will be served through an arrangement whereby those concerned may be settled on the already acquired land instead of procuring additional which cannot be turned to beneficial use and occupancy by the Indians in mind because of their inability financially to establish themselves thereon.”

“…In its final analysis, Mr. Commissioner, kindly understand and know that additional land for homeless Indians of California is not required and therefore further demands on the appropriation for the fiscal year 1930 are not warranted or justified.”

By July 1931, Dorrington had either quit or was transferred or was fired and replaced by Oscar H. Lipps as Superintendent of the Sacremento Agency. Lipps, responding to an inquiry written by Assistant Commissioner J.Henry Scattergood offered specific concerns about the conditions of the homeless California Indians for whom land was purchased.

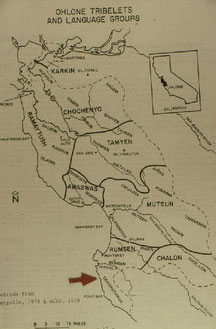

Based on Kroeber(1925), as amended by Levy (1970)

“Receipt is acknowledged of your letter, date June 30, 1931, relating to the matter of purchasing land for homeless Indians of California. …I am addressing this letter to you personally and calling the subject matter thereof to your special attention for the reason that there appears to be a grave lack of understanding in the Office regarding this whole matter of providing homes for homeless California Indians”

“I think it is all the more important that this matter be brought to your personal attention at this time in view of your recent visit to California with the Senate Committee and your familiarity with the sentiment and feeling in this state with respect to the past administration of the affairs of the California Indian.”

“The condition on some of these rancherias are simply deplorable. No one can view many of them and observe the conditions under which the Indians are trying to exist without the feeling that some one is guilty of gross neglect or inefficiency and that a cruel injustice has been meted out to a helpless people under the name of beneficent kindness… And yet there are those who say that I will never do to let the local authorities have charge of the affairs of the Indians lest the Indians be neglected and abuse. …I have not yet seen a single instance where the federal government has done anything like so much for the improvement of the homes and living conditions of the Indians under this jurisdiction as has been done by Sonoma County for the Indians residing for the Indians residing on the Stewart’s Point Rancheria.”

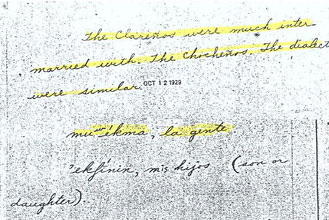

The Clarenos were much intermarried with the Chochenos. The dialect(s) were similar. muwekma, la gente (the people)

“Now it seems to me that the thing for us to do is to look at the facts in the face and admit that in the past the Government has been woefully negligent and inefficient, and then start out with the determination, as far as possible, to rectify our past mistakes. It is difficult to locate the blame, but somewhere along the line there appears to have been gross negligence or crass indifference. If Congress has been honestly and fully advised of conditions and has refused or failed to give reiief asked for, then the Indian Bureau is not responsible for the neglect of the Indians. On the other hand, if Congress believed and intended by appropriating funds for the purchase of lands for homeless Indians and improvements thereon that good and suitable lands would be purchased and houses constructed and improvements made, then we have neglected to do our duty.”

Although the Muwekma Tribe was left completely landless, and in some instances completely homeless, between 1929 and 1932 all of the surviving Verona Band/Muwekma lineages enrolled with the BIA under the 1928 California Indian Jurisdictional Act whose applications were approved by the Secretary of Interior in the pending California Claims settlement.

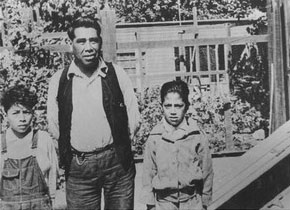

Pfc U.S. Army, 89th Division, 1st Battalion, Co. M, 354th Infantry Regiment, (39 390 899) 1942-1945 WWII

Concurrently, between 1884 and 1934, renowned anthropologists and linguists such as Jeremiah Curtin, Alfred Kroeber, E. W. Gifford, James Alden Mason, C. Hart Merriam and John Peabody Harrington interviewed the last fluent speakers of the “Costanoan” and other Indian languages spoken at the Easy Bay rancherias.

It was during this time period that Verona Band Elders still employed their linguistic term “Muwekma” which means “la Gente” or “the People” In Chocheño and Tamien, the Ohlone (or Costanoan) language spoken in the East and South San Francisco Bay regions

Even before California Indians legally became citizens in 1924, during World War I, Muwekma men enlisted and served overseas in the United States Armed Forces, and four of them (Toney Guzman (pvt. U.S. Army), Alfred (Fred) Guzman (Pvt. U.S. Army), Henry Abraham Lincoln Nichols (Fireman U.S. Navy) and Joseph Aleas (Sgt. U.S. Army) are buried in the Golden Gate National Cemetery. John (Jack) Nichols (U.S. Army) and Franklin P. Guzman (Sgt. U.S. Marine Corps) also served in World War I. Franklin Guzman is buried in the National Cemetery at Riverside, California.

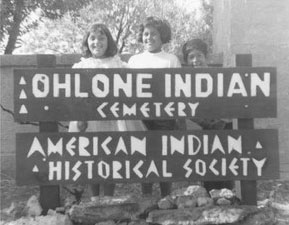

American Indian Historical Society

Lilian Massiatt, Ramona Galvan and Michael Galvan

Fremont, CA, 1966

Guadalcanal, Eniwetok, Marshall Islands, Okinawa, Ryukyu, 1940-1946 WWII

Later, during World War II almost all of the Muwekma men served overseas in all branches of the Armed Forces. Muwekma men and women continued to serve in Korea, Vietnam, Desert Storm and presently, three tribal members are or had served in the U.S. Marine Corps and Army in Iraq. (See the Muwekma Veterans Booklet for more information).

Some of the Muwekma children were sent off to Indian Boarding Schools. Between 1931 and 1940. Lawrence Domingo Marine attended Indian Boarding School at Sherman Institute in Riverside, and there he met wife-to-be Pansy Potts (Maidu Tribe). After completing school, in 1940 Domingo enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps.

Between 1944 and 1947, Jack Guzman, Jr. and his sister, Reyna attended Indian Boarding school at Chemawa, Salem, Oregon, Still landless, and completely ignored by the BIA but functioning as an unorganized tribal band, the Muwekma Tribe maintained its distinctive social ties and culture.

Between 1948 and 1957, the various Muwekma heads of households enrolled with the BIA during the second enrollment period. During the early 1960s, a relationship was forged between Muwekma Ohlone families and the American Indian Historical Society located in San Francisco. The focus of this relationship especially centered on the potential destruction of the Ohlone Indian Cemetery located in Fremont. This cemetery contains over 4,000 converted Missions San Jose Indian graves, including the immediate relations of the Muwekma families who were buried there as late as 1925.

During the 1960s the Ohlone Indian Cemetery was saved from destruction. In 1962, under the leadership of Dolores Marine Alvarez / Piscopo / Galvan and her daughter Dottie Galvan Lameira, they began to mow, clean up and protect the cemetery.

Dolores Marine’s two sons Benjamin Michael Galvan and Phiip Galvan later became important leaders in this effort in 1996, congressman Don Edwards made inquiries with National Parks and the BIA, requesting to place the Ohlone Cemetery as National Monument or into Trust. Both Federal agencies rejected the idea. By 1971, the title transferred to the non-profit tribal entity the Ohlone Indian Tribe, Inc. Afterwards, the maintenance of the cemetery has come under the stewardship of one of the Galvan families.